- Home

- Mike Monahan

Barracuda Page 4

Barracuda Read online

Page 4

About a month earlier, Dr. Collins had received a phone call from a colleague named Dr. Silver, a noted marine biologist who had just returned from Bikini Atoll with a group of scientists on a National Geographic Research Project. During the phone call, he told Dr. Collins that he had seen huge groups of gray reef sharks in the lagoons of Bikini Atoll. He also explained that the corals and wildlife were flourishing like never before, but that there were some anomalies that were probably related to the radioactivity. He informed Dr. Collins of strange-looking fish that appeared to have morphed over the past fifty years to adapt to their radioactive environment. Dr. Silver knew that this information would intrigue his ichthyologist pal.

Dr. Collins immediately applied for a grant to study the gray reef sharks of Bikini. The museum’s board of directors was leery of the project, but Dr. Collins convinced them that it had great merit, explaining how the reef sharks had been consuming radioactive fish for fifty years and that this could have caused them to evolve differently than gray reef sharks in other oceans. The sharks may have overdeveloped senses that would make them better hunters; they could be larger and faster, producing superior offspring. The possibilities were endless. No one knew the exact effects of long-term exposure to radiation or the consumption of radioactive food, which was known to be certain death for humans. Sharks, however, were descendants from a long line of prehistoric fish that didn’t get cancer. Dr. Collins finally had a chance to study these prehistoric subjects. For all anyone knew, a cure for cancer could be one of the many results of his study.

He received the grant and notified his assistant of three years that they were off to the South Pacific to make ichthyology history. James was quietly as enthusiastic as his neurotic litterateur.

The trip to Shark Alley Island was an adventure in itself. Dr. Collins was very direct and strong-willed about all things in life, not just his work. He abhorred incompetence and tardiness, was extremely opinionated, and was unwilling to accept excuses. Naturally, Murphy’s Law struck them on numerous occasions while traveling from Miami to Micronesia, so James had to play referee many times. The professor’s neurosis caused an unnatural belligerence that resulted in heated arguments amongst most people with whom he had social contact. He was not a “people person.” He thought better of cold-blooded sharks than warm-blooded humans.

With the help of the grant, the two scientists stayed in the luxurious Majuro Majestic Hotel on Shark Alley Island instead of roughing it at the Bikini resort. James was quite comfortable with this arrangement. He and Dr. Collins had adjoining rooms, so they could work together and still have their privacy. There were only a handful of other divers since the hotel wasn’t quite ready to open to the general public, but it was still rather lavish. The grand opening was still a week away, and the team of shark scientists relished the solitude.

Dr. Collins still had his nose deep in his research papers while James undertook the unpleasant task of unpacking. First, he unpacked their research materials and placed them in their proper categories. This was a meticulous job, but when done right, it avoided the redundancy of time-consuming searches.

Then he unpacked the suitcases, quickly and methodically placing the contents into the dresser drawers and closets. He unpacked and laid out the scuba gear they would be using. This was a labor of love for James, who was a master diver and took great care in handling his equipment. He was equally diligent with Dr. Collins’ rigging.

James placed his dive apparatus on the bed, scrupulously dusting and cleaning each piece before hanging it in the closet. He gingerly handled his hoses and blew dust from his second stage regulator. His regulators were made by Sherwood, a top of the line model that could be used in either ice or tropical diving. He checked the hose to make sure there were no kinks in it. He also tested the rubber mouthpiece that would fit into his mouth while breathing through this second stage. It was solid and there was no dry rot, so he knew it would suffice for the upcoming dives. He then checked his Octopus second stage. This was also a Sherwood product. The Octopus was an emergency second stage to use in the unlikely event that the primary one failed. The mouthpiece and hose were also in good condition.

James delicately handled his first stage and cleaned it. The third hose that was connected to the first stage held his dive computer. James preferred the U.S. Divers brand of dive computer because of its simplicity. Some brands had many bells and whistles but were too complicated to read or understand when in dark waters or at depth.

James loved his dive computer because it gave easy-to-read grafts to prevent him from staying underwater too long. U.S. Divers was also recognized as one of the more conservative computers, and James liked this added safety feature.

He tested the battery on his dive computer and was satisfied that it was adequate. Then he carefully hung the regulator on a hook in the closet and allowed the hoses to hang freely.

Satisfied that his dive gear was clean and safe, he repeated the process with Dr. Collins’ equipment, complete with a state of the art re-breather bubble free system. With the research paper, clothes, and scuba gear unpacked, James felt hungry.

“Hey, Professor, how about some dinner?”

“You go. I’m busy. I’m busy.”

“Okay, Dr. Two-Times.”

“Did I do it again?”

“Yes, you did. Let’s take a break and feed our brains.”

The professor mumbled something unintelligible but followed James to the elevator. The scientists were on the fifth floor of the five-story hotel. They had a grand view of the east side of the atoll and could see clear across to Bikini Island. The elevator took them to the lobby, and they followed the arrows to the dining room.

“This is quite a setup,” James commented. “It must have taken them a few years to get all this interior and exterior design together.”

The professor nodded. “Yes, it’s nice,” he mumbled. “It would be nicer if there weren’t so many damn Japanese people around here.”

James let out an uncomfortable laugh. The majority of the staff was Japanese, except for the pretty liaison woman and some of the hotel managers, who appeared to be Russian. That probably didn’t sit too well with many of the locals. James made a silent prayer that Dr. Collins didn’t allow his opinionated sarcasm to cause problems with the hotel staff.

A nice Japanese waiter seated the two at a window table and brought a pitcher of ice water. While James read the dinner menu, Dr. Collins was busy making notations in his journal. The professor never went anywhere without his beloved journal.

“Will you please put that away and start enjoying yourself, Doctor?” James lamented.

“We are here on a grant and our mission is quite clear,” the professor snapped back.

“You must eat if you want the gray cells to be active in that mad brain of yours,” James pressed. “It also wouldn’t hurt if you took the time to stop and smell the roses once in a while. Just look about you. This is paradise.”

Dr. Collins looked blankly at his protégée, and then slowly put his pencil in his shirt pocket and closed his journal. Looking out the large bay window, he noticed the magnificent view of lush gardens leading down to the dock. The dive boats and fishing boats were rocking gently at their moorings as the setting sun splashed a river of gold and red hues across their bows. The low cirrus clouds were speckled with the flight of sea birds returning to their nests.

The professor’s eyes widened as he took in this portrait of nature entering its nocturnal state. The golden sun would fall below the crimson horizon in just a few minutes. A waiter broke his trance when he asked the pair for their dinner order.

Dr. Collins watched the waiter as he left and saw the regal opulence of the dining hall for the first time. The hall was littered with ornate pillars and high ceilings. Bright pastel colors abounded, except for the muted murals that depicted fishing villages and native life. Centerpieces of fresh flowers were lavishly placed in an ever-widening circular fashion.

�

�Beautiful, isn’t it, Doctor?” James asked.

“I’ve seen better,” Dr. Collins crackled in sarcasm.

James knew that the professor would never admit when he truly liked something unless it had a dorsal fin and teeth.

***

“The boat leaves in ten minutes sharp, so get your gear aboard now,” Steve ordered.

Steve Crachie was the senior dive master at the Majuro Majestic, and it was his responsibility to make sure that the divers stayed safe. Thus, it was his responsibility to get the divers on board and check their dive gear before allowing them to dive. He also had to check their scuba diving credentials and make sure they had the proper safety equipment. Just as important was making sure that the divers did not touch or remove any dangerous materials from the shipwrecks. These warships had been sunk fully armed with weapons containing high explosives. Fifty years of salt water had slowly deteriorated these weapons, making them quite unstable. Divers always wanted to retrieve a shell for a souvenir, but that was like bringing a live hand grenade on board the dive boat—or worse, back to the hotel. It was Steve’s job to ensure that the live, unstable ammo on board these graveyard ships remained undisturbed.

Steve was a Canadian with all the necessary credentials. Besides being the head dive master, he was a licensed PADI dive master, TDI Trimix diver, TDI gas blender, TDI Trimix blender, TDI decompression producers instructor, and advanced wreck instructor.

A group of divers had arrived at the Majestic that afternoon for a week of diving. Ten had signed up for the initial checkout dive, and they were clambering aboard the dive boat Lily I, jockeying for position. The Lily I was a Hammerhead front-loading dive boat with a length of twenty-five feet and a beam of ten feet. It had an aluminum deep-V with a drop front gate and a side ladder. Its benches accommodated twelve divers.

“It’s only a ten minute ride to the USS Saratoga,” Steve instructed. “The Lily I will tie up to the bow mooring line. When Captain Jonas gives us the okay, we will gear up. Dive Master Carol and I will check your air and gear before we enter the water. When we enter the water, we will all remain on the surface until I give the signal to descend.” He paused to make sure everyone understood and saw nods all around.

“I will lead the way down the mooring line to the deck of the Saratoga and Carol will follow last. Once on the Saratoga deck, I will motion to each of you to make sure you are okay. I want you each to signal back to me. If there is a problem with any divers, Carol will escort them back to the Lily I. When I am convinced that everyone is okay, we will drop over the side of the Saratoga and float down to the lower decks. I will lead the dive and Carol will follow.

“I don’t want any diver going below me, leaving the group, or picking anything up. We will follow my dive profile according to my computer. When the first diver gets down to fifteen hundred psi of air in their tank, let either Carol or me know. We will begin our slow decompression ascent at that time. Captain Jonas will have air tanks hanging at various stages of ascent should they be needed. Any questions?”

“How deep will we be going?” a young lady asked.

“I’ll decide that based on the visibility and how tight a group you swim in. Safety is my number one concern here.”

“Can we penetrate the wreck?” another diver queried.

“Not this wreck,” Steve answered. “Unfortunately, the carrier collapsed in on itself many years ago, probably due to its enormous weight. All the previously open areas have become crushed, so they’re too tight for divers to safely enter and exit. It’s really a shame because there are loads of fighter planes and tanks on the lower levels. We hope in the future to get some acetylene torches and cut holes in the side of one of the lower cargo holds so we can see if it is safe to explore the interior. Since the ship has been here for more than fifty years, we suspect that it might still be too dangerous to penetrate because of fear of falling debris and shifting machinery that is not bolted down. Penetrating large shipwrecks is inherently dangerous under ideal conditions, so today we will just explore the exterior.”

Captain Jonas started the engines, and soon the Lily I was crossing the atoll headed toward the final resting place of the heroic USS Saratoga. Carol helped tie the dive boat to the mooring ball, and Steve told the divers to gear up.

Billy and Bob, two Australian brothers, were the first to put on their gear. As they did so, Billy muttered to his brother, “Shit! I thought we might get to see some old World War Two planes.”

“Well, maybe we will,” Bob replied quietly.

“How? You heard what Steve said.”

“They can’t keep an eye on ten divers all the time. If there’s a hole big enough to fit through, I’m going in. This Canadian girlie man isn’t going to stop me.”

“I don’t know, Bobby. You heard what he said about stuff falling and shifting all the time.”

“C’mon, Billy, we didn’t come all this way and pay all this money to look at the outside of an old rusty boat, did we?”

“I guess not,” Billy murmured.

“Are you guys ready?” Steve asked the brothers.

“Yup,” they answered in unison.

Steve checked that their air tanks were turned on, their gauges were working, and their computers were on. “In you go, but wait at the surface for the rest of us.”

Billy and Bobby duck-walked to the rear of the boat, and Billy took a giant stride into the water. He submerged several feet and then bobbed to the surface, patting his hand on top of his head, the universal diver signal indicating that he was okay. Billy kicked his fins to get out of the way so Bob could take a giant stride.

With all twelve divers on the surface, Steve said, “When I give the divers down signal, I want everyone to vent air out of your buoyancy compensator—that’s BC—vests and follow me down the mooring line.”

He gave the thumbs-down sign, expelled air from his vest, and slowly sank into the clear blue South Pacific water. When he was down ten feet, he watched the others as they slowly sank. All looked good, so he inverted his body and descended headfirst to swim to the mooring line that led down to the flight deck of the Saratoga.

Once he arrived at the huge flight deck, Steve glanced up at the new divers looking down at the silent warrior vessel. He knew that this was a great checkout dive for divers who had just arrived at the Majestic hours ago. It was barely past three o’clock, and the weary travelers were descending into a watery time warp. Less than one hundred divers had yet to have the pleasure of standing on this deck in the past fifty years, and these descending divers would soon join that illustrious group.

It was like watching a movie in slow motion as the divers glided down past the aircraft carrier’s bridge superstructure, silhouetted against the afternoon sky above. The visibility was in the one-hundred-foot range, and the fish life was active. Steve saw the silhouettes of several sharks and schools of diverse fish, from small baitfish to the larger pelagic fish that were so abundant in this tropical water.

Once the divers were all kneeling on the flight deck at a depth of one hundred and fifteen feet, Steve went up to each diver to give the okay signal. Each diver, in turn, returned the signal.

Then Steve slowly swam to the bow of the massive carrier and bobbed headfirst down into the abyss. When he reached the front torpedo tubes, he stopped and looked at his dive gauges; he was at one hundred and forty feet, and his bottom time was near three minutes already. He waited for the rest of the divers to catch up to him and then pointed to the once deadly torpedo shafts of death. After each diver got a good look, Steve continued swimming back toward the stern pointing out various parts of the ship’s hull and compartments that were crushed shut. He pointed to several large green moray eels that had made the crevices their home. He even gently pulled out a small octopus that occupied a hole in a piece of metal tubing. The octopus immediately began changing colors to adapt to his surroundings as Steve let the creature float within the group of inquisitive divers.

Bill quic

kly reached out to touch the octopus, and as if sensing aggression, it darted away in a spray of black ink that left a dark cloud in its place. Steve shook his head disapprovingly at Bill and continued the underwater tour.

The divers were able to get up close and personal with the USS Saratoga. They could see and touch her corroded hull, and see the reddish colors produced by years of oxidation. The many levels of the hull looked like someone had stepped on a child’s dollhouse and crushed it. Groupers, angelfish, snappers, and many other kinds of fish swam in and out of the small openings of this now dormant centurion. The once sleek lines of the hull were buckled, and sharp edges were precariously protruding. Thin sheets of fishing nets ominously shrouded the wreck. Steve pointed out each hazard to the divers as they were encountered.

At one point, he shone his dive light through one of the larger openings. A large hatch cover was bent in an outward concave position allowing a three-foot opening. It was large enough for the divers to stick their heads into for a look but too small to enter with scuba tanks. The light beam could only penetrate for about four feet into the darkness, but each diver could see the numerous dangling beams and cables that made the interior of this cargo room resemble a huge spider’s web of death. Colorful fish darted about anxiously when the light beam hit them. Bob and Bill showed a special interest in this cargo hatch as they pushed and pulled at the hinges that held the ancient hatch in place. Steve had to tap them on the shoulder and motion them to follow him.

The dive master remained on alert and frequently checked his dive computer. He knew that this diver operation was in its infancy and that an underwater tragedy could cripple its future, so he followed a conservative dive profile. Soon he was once again ascending from the lower depths up to the flight deck. He arranged his divers in a circle, pointed to the bridge, and motioned that it was the next point of interest. Then he shot a blast of air into his BC vest and slowly ascended toward the bridge. As he rose, he watched as the other divers did the same and Carol followed up the rear.

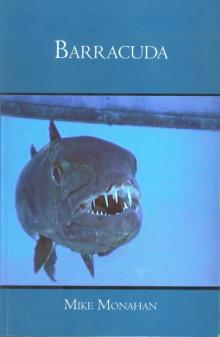

Barracuda

Barracuda